Climate Reprogramming

By Anthony Brower, Wyatt Frantom

The relationship between climate change and urban design is rapidly evolving. The challenge for designers is to understand the most efficient and cost-effective ways to use available technologies. Façade design is one example where performance, technology, and code changes come together to positively impact the environment; and our first targets in this endeavor should be existing building stock, where a vast majority of our energy consumption originates.

We challenged our 2018 summer interns to tackle these issues as a design problem with an overlay focus on adaptation and form. The task was to redesign four existing building envelopes in downtown Los Angeles by studying four different possible conditions for improving building performance: internal program-driven solutions; city-edge factors; exterior transitional zones; and optimizing the site’s relationship to the sun. Design interns partnered with engineering interns to demonstrate the power of integrated performance modeling at the speed of design with respect to how each of these properties interacts with the urban fabric. Their first question to address was how can we think about façade design differently.

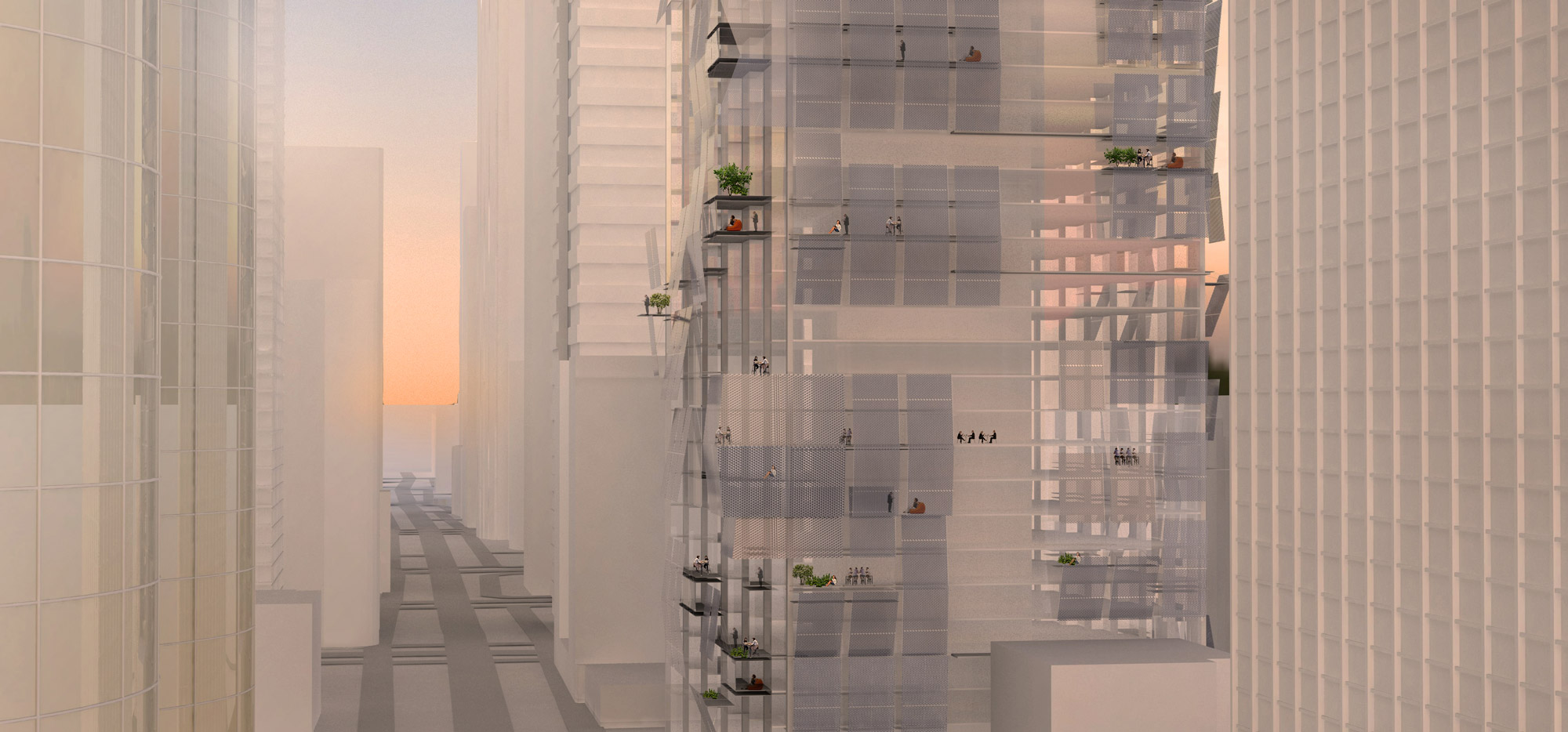

When we think about envelope design, the initial parameters for design usually come from the exterior environment. Sun, wind, orientation, etc. A lesser known factor is the internal building program or use. Some programs are more amenable to building shading than others. One team combined a building program mix of mission critical use, which has minimal need for exterior views, and supporting office space where right to light is a key factor. The team embraced the disparate program needs to organize the building vertically. By placing server systems on the south side and orienting office spaces to the north, the team allowed program to be expressed on the building exterior providing external shading and natural light where they were needed most.

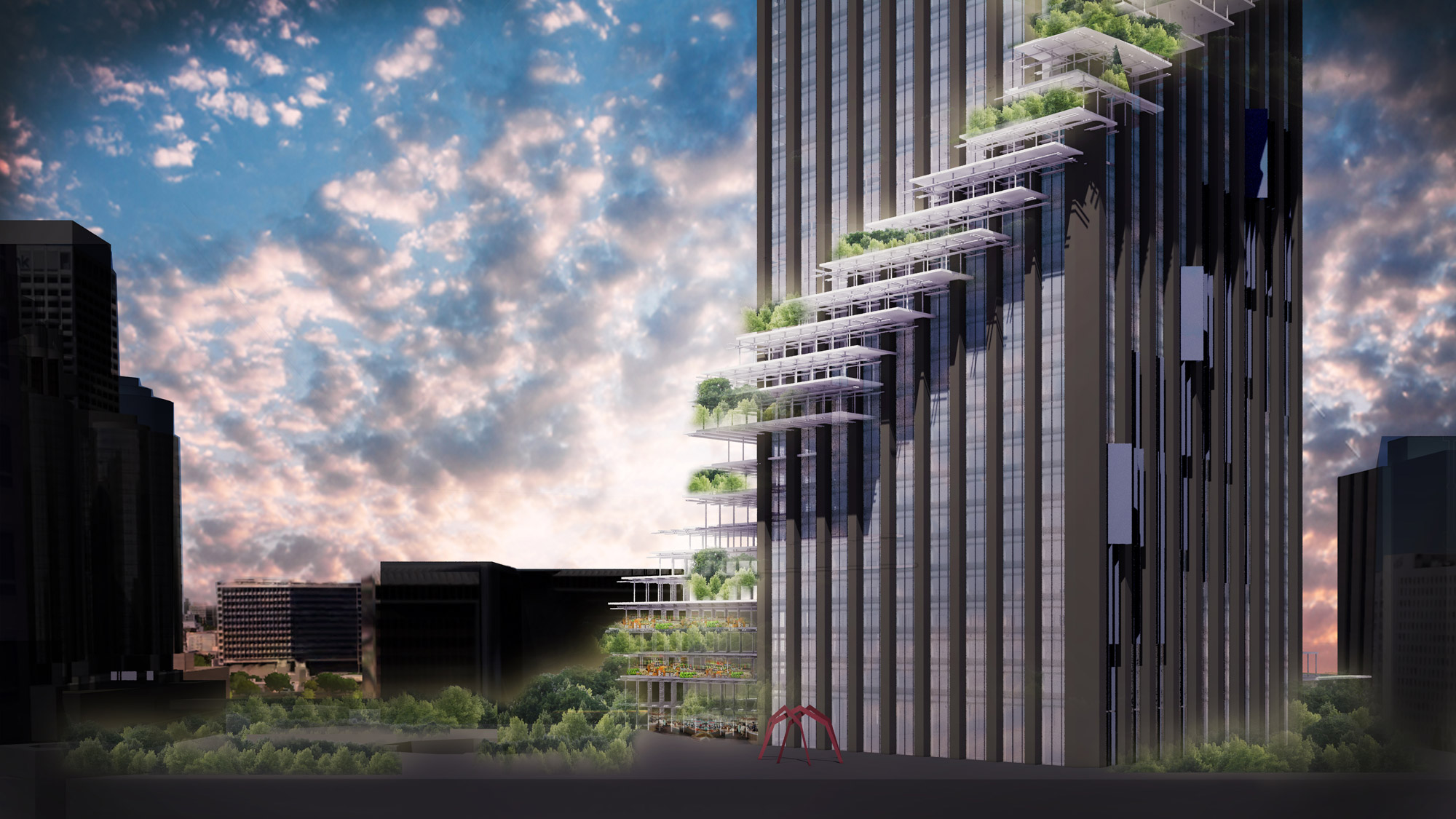

The structures at the edges of cities need to take a modified approach compared to many urban core buildings that rely on shading from their neighbors. Highways are traditionally thought as separators of communities. In this condition, 19 lanes of traffic — as well as several access ramps and an adjacent landscaped buffer — combine to create a sizeable gap between buildings larger than a city block. Without neighboring buildings to provide shade, the city perimeter condition façade is bombarded by an extended duration of heat loading. Self-shading for buildings can be a challenging prospect as this condition also fights with acoustic issues related to traffic and the emissions.

Building performance improvements often require designers to think about the problem differently. A new animated public interface made up of semi-outdoor spaces shielded by a folded, perforated metal mesh formed the solution for this team's take on occupying the building skin.

Oriented along the compass points, this existing building stands out defiantly from the city grid, which our interns capitalized on with their bold and standout proposal. This team proposed replacing the dated bronze glass with high-performance glass to achieve dramatic energy savings and daylighting improvements. Each façade is strategically shaded to maximize views out, address solar orientation-specific shading requirements, and preserve the historical character-defining features of the existing façade. Most dramatic is the team’s bold approach of springing off from the plaza where the weekly Farmers Market is held, and spiraling humanity up the brutalist tower with filigreed, occupied terraces.

Our interns benefitted early and often from the collaboration with their engineering counterparts. They navigated immense number of factors to analyze and address the conditions together. The engineering interns performed more sophisticated analysis of the existing building envelopes than typically available during the conceptual design phase. This difference helped narrow the range of possibilities, and focused our process on the most promising and potentially impactful design strategies.

It was exciting to see the discussions between both design and engineering students as they learned from each other. Architecture students pointed out significantly reduced heating and cooling loads, while engineering students argued the merits of the proposed design solutions. Each team’s progress was validated as the design solutions evolved and course corrections were made in near real-time. The final presentations confirmed the sense of co-ownership and co-authorship. This is just the kind of collaboration our practice needs to navigate the future demands of climate, technology, and code.

- Cassidy Vida, USC

- Christine He, USC

- Cyrus Chu, MIT

- Hooman Alinejad, Cal Poly Pomona

- Kaarina Nehring, Northern Arizona U

- Kunyu Luo, USC

- Massimiliano Boselli, Sci-Arc

- Milena Milich, Cal Poly SLO

- Sam Crawford, UCLA

- Vishant Kothari, Columbia

- Wei Tse Yuan, Sci-Arc

- Yifen Zhong, MIT

- Anthony Brower, Gensler

- Audrey Wu, Gensler

- Marcus Richeson, Gensler

- Wyatt Frantom, Gensler

- Colin Schless, Thornton Tomasetti

- David Herjeczki, Gensler

- Edgar Lopez, Gensler

- Joe Tarr, Gensler

- Justin Di Palo, Syska Hennessy Group

- Mark Chu, ARUP

- Michael Pedersen, Gensler

- Brian Fraumeni, Gensler

- Craig Shimahara, Shimahara Illustrations

- Gijs Libourel, Thornton Tomasetti

- Heather Spearman, Gensler

- Jared Shier, Gensler

- Michael Frederick, Gensler

- Paul Andrzejczack, Gensler

- Robert Garlipp, Gensler

- Russell Fortmeyer, ARUP

- Seth Strongin, ARUP

- Som Iempinyo, Gensler

- Michael Martin, Gensler

- Andrew Dalton, Gensler