How Climate Change Impacts Our Health

September 18, 2020 | By Mallory Taub and Oliver Schaper

As we grapple with the immediate and long-term impacts of the current global health pandemic, it can be challenging to think about climate change with the same level of urgency. But if anything, the pandemic has shown us how being unprepared for a global health crisis can lead to widespread mortalities and bring the global economy to its knees in a matter of months. Climate change has a direct impact on our health and wellbeing now and it will become only more acute in the future. The fires that are devastating California, Washington state, and Oregon provide the latest reminder.

Because the building and construction sector contributes the highest emissions globally each year, the time is now for interdisciplinary collaboration that works towards impacting both climate change and health at scale.

As part of our Earth Week 2020 programming, in April Gensler moderated a virtual panel with researchers and policy makers in our New York office that focused on how climate change impacts health. Panelists included Laurian Farrell, of Global Resilient Cities, Professor Thaddeus Pawlowski, of the Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes at Columbia University, Manuela Powidayko of the New York City Department of City Planning, Daphne Lundi of the New York City Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, and Professor Prathap Ramamurthy, of the Urban Flux Observatory at the City University of New York.

Here are ideas that emerged from the conversation about three impacts of global warming, including rising temperatures, air pollution, and severe weather, plus, a look at how they impact health, and how the role of the built environment can evolve to enable a more resilient future.

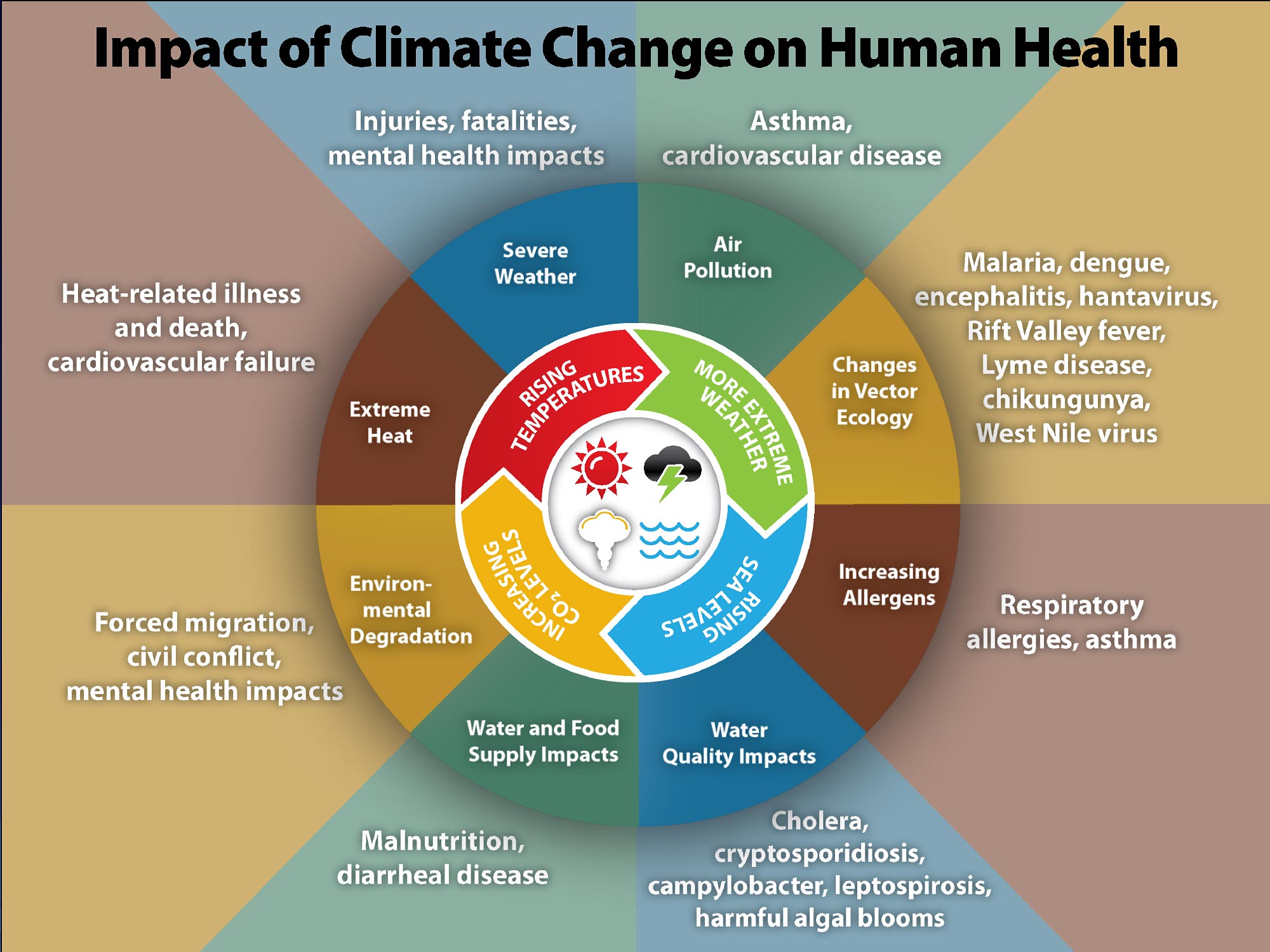

Climate Change and HealthOrganizations and institutions including the World Health Organization, the International Panel on Climate Change, and the Harvard School of Public Health have widely explored and documented the intersection between the impacts of climate change and public health.

According to these experts, climate change causes a variety of shocks and stressors that negatively impact health. Examples include asthma caused by air pollution, mental health issues stemming from the effects of degraded living environments, and cholera caused by poor water quality. In the face of increasing hazards, risks, and vulnerabilities, some solutions focus on mitigating negative impact and others on adapting to changing conditions.

In discussing how to design for the future with the panel, Columbia’s Thaddeus Pawlowski defined resilience as "empowering communities and ecosystems to survive and thrive in a world in crisis.” Today, nearly 100 cities are collaborating through the Global Resilient Cities Network to identify climate risks, share resilience strategies, and implement adaptation efforts. Our panelist from Global Resilient Cities, Laurian Farrell, shared that cities are on the frontline of dealing with the impact of climate change — and because nearly 7 out of every 10 people are projected to live in cities by 2050, this issue is of growing importance.

Health is essential to survive and thrive, and as design practitioners, we must understand the connection between the built environment, climate change, and health in order to drive change and promote resilience.

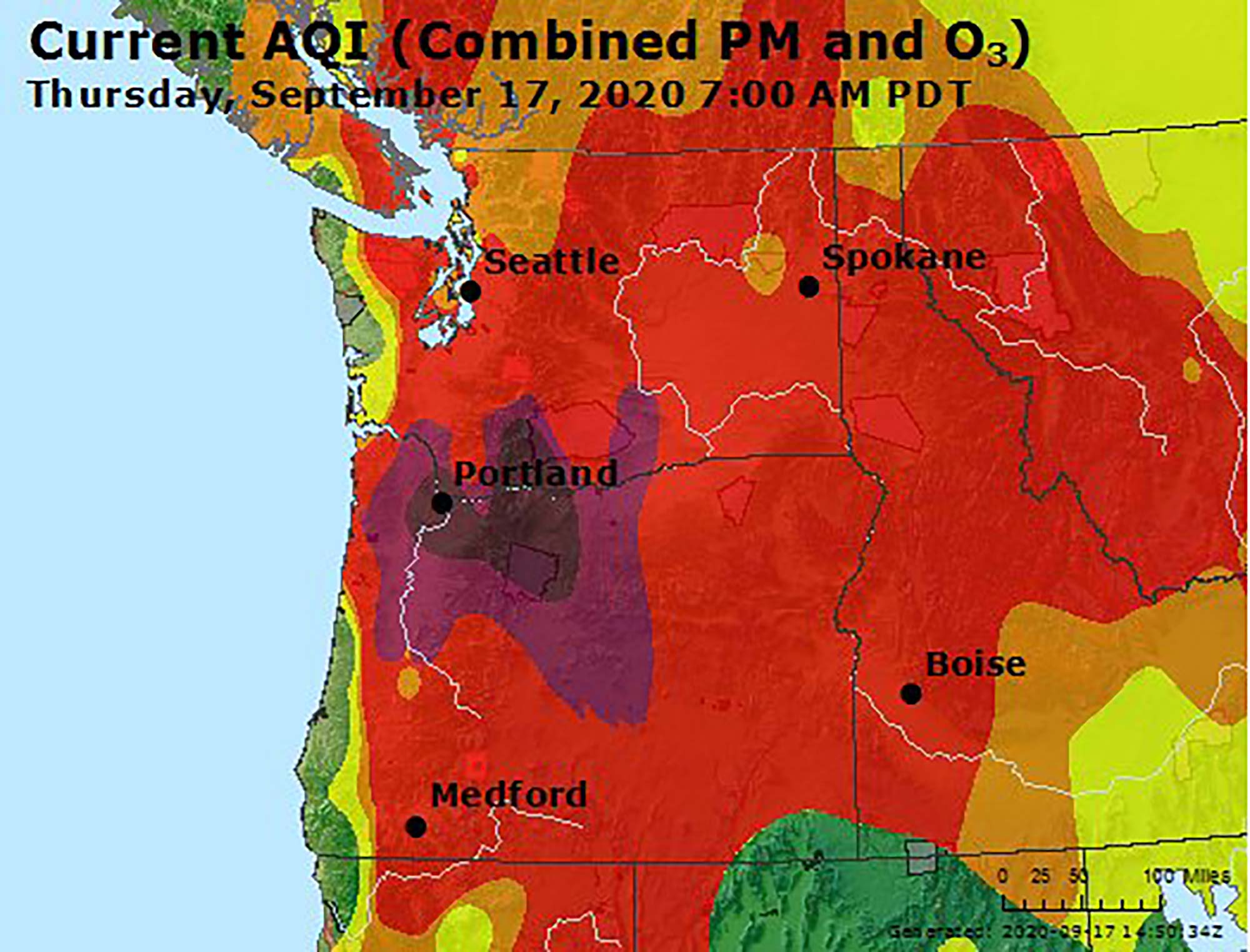

Health Impact of Rising TemperaturesThrough the rise of hotter and drier weather as a result of climate change, wildfire risk has significantly increased. Six of California’s 10 largest wildfires have happened since 2018 — and five of those fires occurred this year. The numerous associated health impacts with these fires include increased risk of mortality, respiratory disease, and cardiovascular disease.

While building design can help make structures and communities more resilient to exposure to smoke and dangerous air quality levels, driving down emissions globally from the building sector will help to prevent the risk from further increasing. The Rocky Mountain Institute advocates for eliminating fossil fuel use in the built environment as the only way for California to meet its carbon goals by 2045.

For our part, Gensler introduced the Gensler Cities Climate Challenge (GC3) at the UN Climate Summit in 2019 as a way to commit to making our design work carbon neutral by 2030, and to challenge the design industry as a whole to do the same. As designers, we can significantly reduce the total fuel required to operate buildings, design buildings to be all-electric, or electric-ready, and help advocate for a rapid transition to clean electricity.

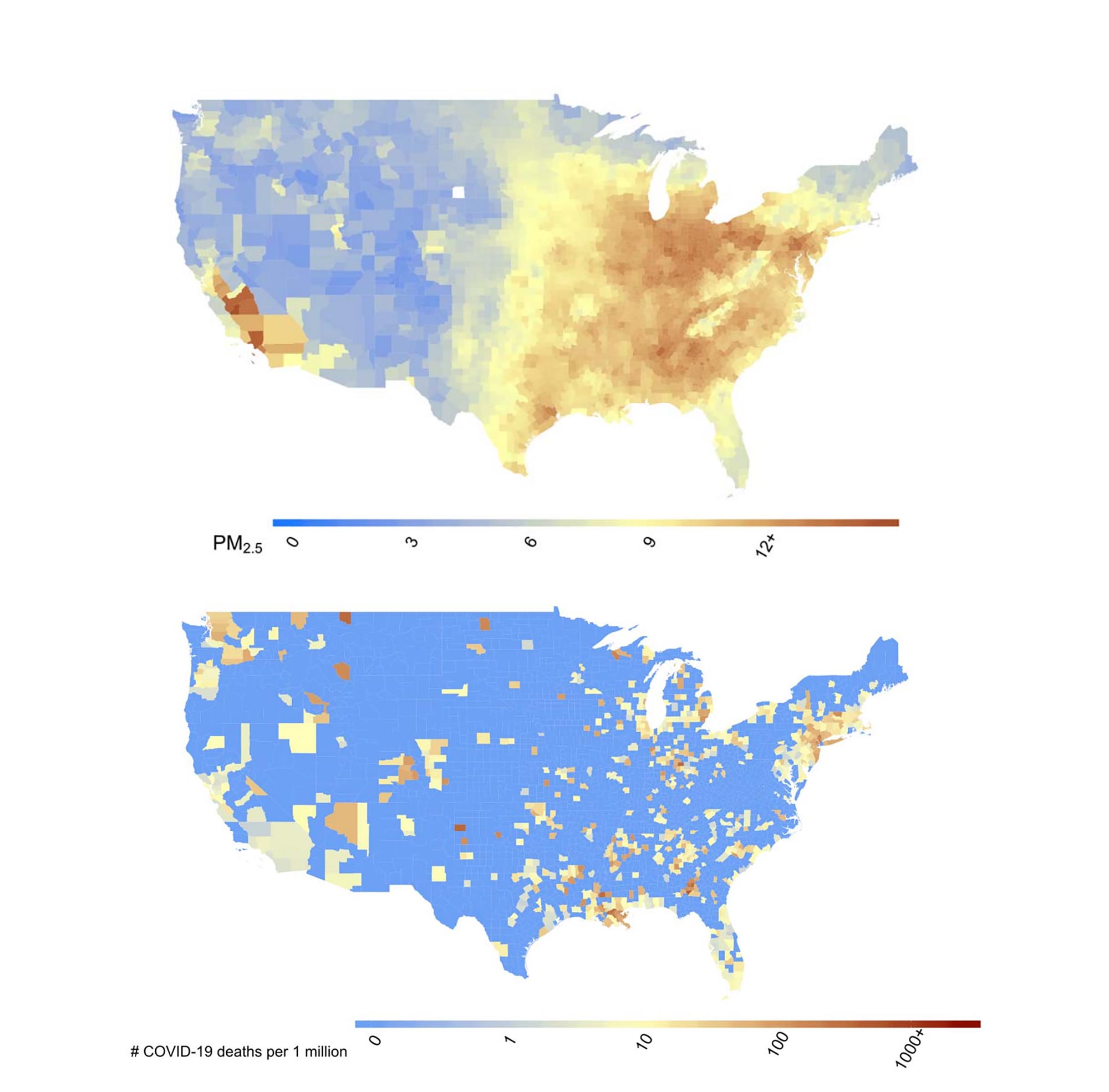

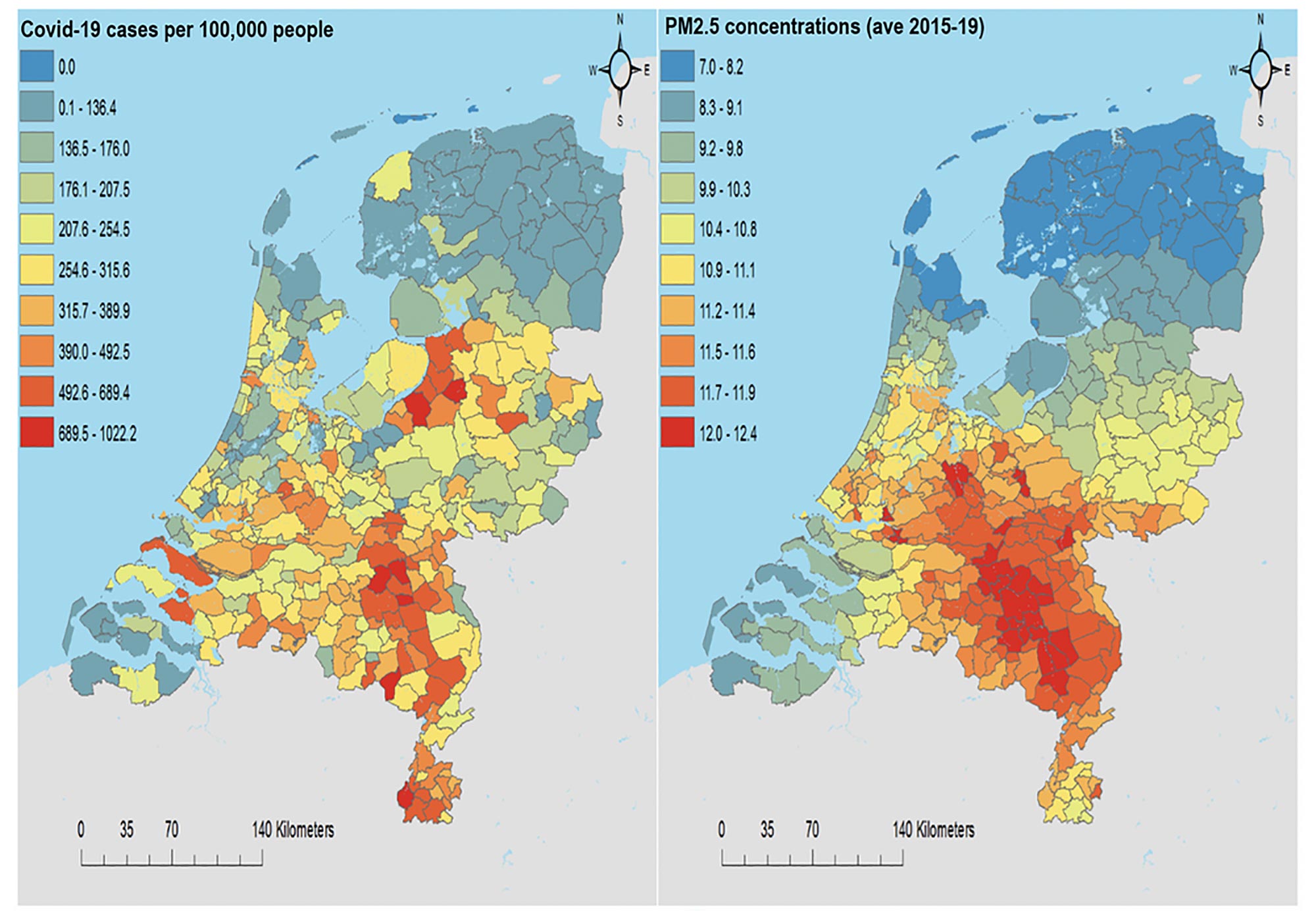

Building emissions contribute to air pollution, and long-term exposure to air pollution has been linked to higher risk of mortality from COVID-19. It’s not just the operations of buildings that contribute to emissions, but also the embodied carbon of construction materials. For example, rebar produced by coal can have up to six times the embodied carbon as rebar produced by hydroelectric power in the Pacific northwest.

Architects can reduce embodied carbon by repositioning existing buildings, and when it comes to new construction, they can prioritize using lower carbon materials like timber, design structurally efficient buildings to reduce the total materials needed, and select building products with low embodied carbon. Architects can also advocate for industry partners and manufacturers to disclose the embodied carbon of their products.

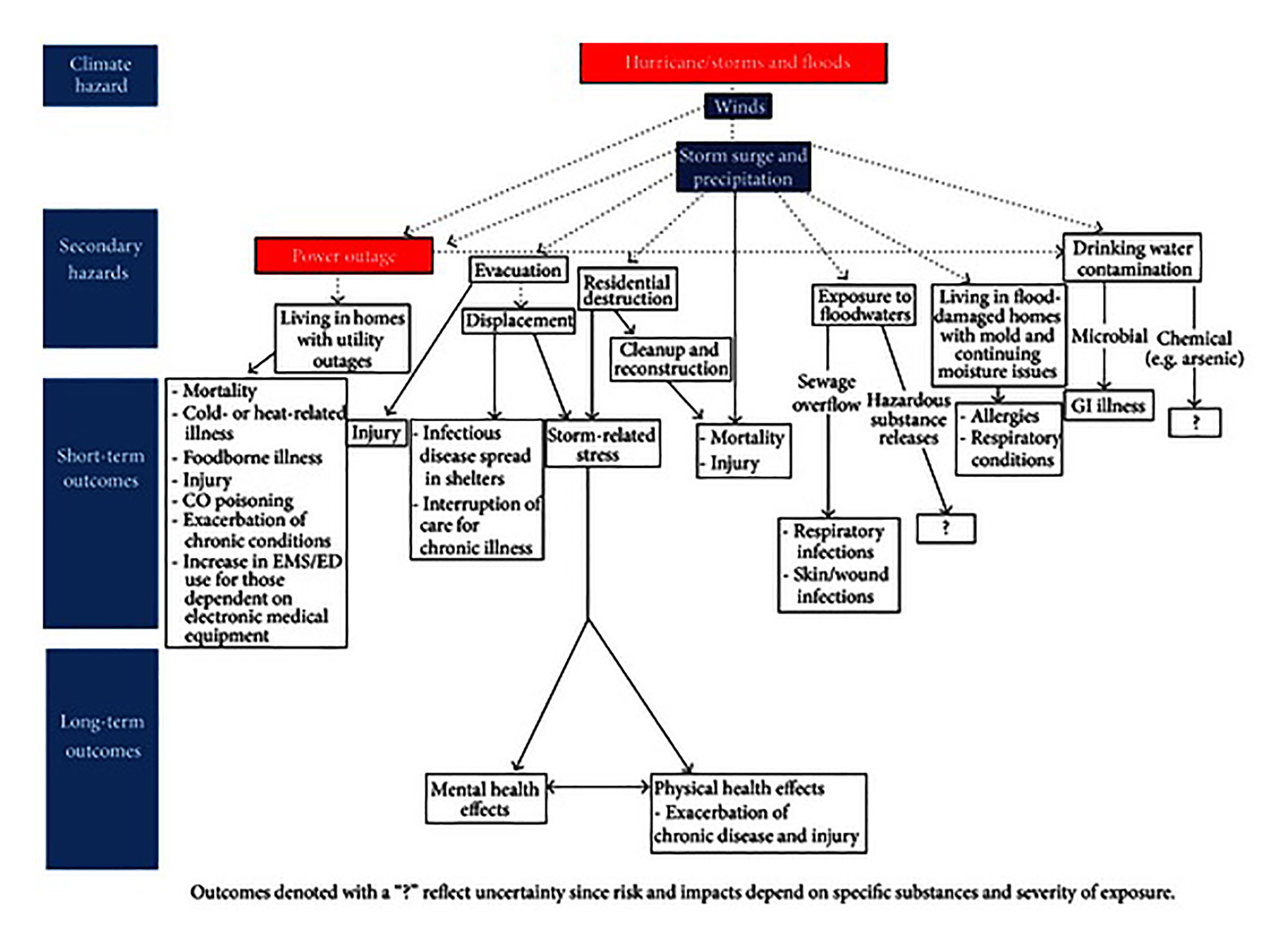

Researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have found that global warming will increase rainfall and intensity for tropical cyclones, which includes hurricanes and typhoons. Many tri-state residents recall the terrible impact Superstorm Sandy had on the greater New York City area in 2012, including loss of life, environmental and property destruction, and impacts on the health infrastructure — but there were also long-lasting impacts on health as a result. Six months after the storm, almost two-thirds of flooded households still contained mold and associated adverse mental health issues increased.

In response, the following year building codes and zoning were updated to help mitigate the impact of future storms in the built environment. These changes incorporated flood-resistant construction standards, such as minimizing the types of acceptable spaces below the design flood elevation (DFE) and guidance for dry floodproofing and the location of mechanical equipment.

In our panel, Manuela Powidayko, Project Manager for Zoning for Coastal Resiliency at the NYC Department of Planning, reflected on what planning for flood risk management means for the density of our cities, asserting that adaptability and flexibility are key.

“If we really want to tackle environmental justice and good design and allow everyone to have access to good homes and services, we need to shift how we are thinking and planning for density, and how we design units, and how we design regulations for buildings,” said Powidayko. “Instead of thinking about quantity of housing stock, we should be thinking about density through the lens of scalability. If you are able to have regulations in place that do not put a max or actually plan for a building to be built with a number of units, and allow that building to incorporate more families with time, that’s how we should be planning ahead.”

The health of vulnerable populations is disproportionately at risk from the impact of climate change, primarily those with the weakest health protection, according to the International Panel on Climate Change. That is why it's critical that architects and designers address historical and systemic inequities and deliberately shape the built environment to further climate justice by taking actions that can improve air quality, mitigate the impact of extreme heat, and help create an inclusive, clean economy that provides equitable job opportunities.

During the panel, Daphne Lundi from the NYC Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, raised an important point, noting, “In order to be in a place where we are actually addressing climate threats, we need to be addressing histories of inequality. In all cases of disasters that we have experienced in the past, people who are better off, are better off, and people who are not better off, are struggling and that’s never going to change regardless of the hazard. But what can change is our ability to support those vulnerable populations, so they are not at the fringes when events happen.”

This was echoed by Thad Pawlowski, who added, “the scales of inequality that have been out of control for my entire life have reached a fever pitch at this moment [and] are no longer tolerable.”

ResilienceIn thinking broadly about creating a more resilient future, the panel focused on two big ideas, noting that a strong sense of community improves resilience, and acknowledging how important it is for individuals to understand the impact of climate change on their own health.

Panelist Daphne Lundi explained how the NYC Mayor’s Office of Resiliency’s “Be A Buddy” program is promoting community resilience. The program links social service and community organizations, volunteers, and at-risk New Yorkers. During extreme events, such as a tropical storm or extreme heat wave, this network is activated to connect neighbors to those at more risk.

Establishing lines of communication between neighbors through the Be a Buddy program strengthens social cohesion and helps connect isolated people to existing city services such as cooling centers.

“What we’ve seen is that people who have strong networks and strong social ties are often in the best position to recover and go back to normal after a disaster,” said Daphne.

The complex link between climate change and health can be easier to break down and understand by making a connection personal to how the health of our surrounding environment has a direct impact on our individual wellbeing.

One of our panelists, Professor Prathap Ramamurthy, observed a significant generational difference in understanding a sense of urgency when working on research on the impact of extreme heat in New York City. He found that ninth and tenth graders were extremely motivated to be part of the climate movement but he encountered challenges when it came to working with adults on a project to install temperature and relative humidity sensors in their apartments to raise awareness about extreme heat indoors during heatwaves. He explained, “People don’t always think far ahead and that needs to be bridged. Older generations don’t always see the direct connections and we need to do a lot of work in this aspect.”

ConclusionAs architects and designers consider how the current health crisis is transforming our world and challenging the wellness of our cities and public spaces, we cannot regard climate change as a separate issue. Climate change and public health are directly related and intersect, and it’s critical that we address climate change now to help improve health both immediately and in the future.

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing recovery planning offers a serious look at what can happen when there is no preparation in place for sudden shocks, but it has also shown that adapting and implementing substantial changes to the way we live, work, and play is possible.

Thaddeus Pawlowski expressed optimism during the panel, noting, “We can, in fact, change and it is fantastic to see how rapidly we have all changed our behavior and not just for our own benefit, but also for the benefit of the people we don’t know who might be more vulnerable to COVID-19.”

In these current times of disruption, we are at an inflection point as we consider how we can reimagine our communities to become more resilient to climate change, especially those that have historically been marginalized, in order to ensure a healthy future for all.

“We need to critically identify what we do not want to go back to” in a post-pandemic climate, said Laurian Farrell, of the Global Resilient Cities Network. “We have an opportunity here to design a future and we have to set the bar high and make bold moves, which is extremely difficult working across so many systems, but if we can think of this in these simple terms, and start pushing the needle forward in the right direction, then that’s our best chance at success.”

For media inquiries, email .