Inclusion by Design: Insights from Design Week Portland

By Gensler Portland

Gearing up for our annual Design Week Portland event, our studio is reflecting on our successful event from 2019 and the lessons we are taking away to improve our design process. To create inclusive, meaningful, and impactful places, we need to consider how we approach and what imprints we leave on the communities our design work is meant to house, serve, and engage.

Gensler hosted a panel of thought leaders, designers, and educators from across industries and cities to discuss inclusion through the lens of design. Our goal was to foster meaningful and honest conversations around diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). In the process we confronted the ways in which design fails to address DEI while identifying opportunities to leverage design to create places, things, and experiences that holistically respect and value differences across race, religion, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, age, ability, socio-economic status, or any other characteristic that may present a barrier.

Holding difficult conversations — and actively listening — is a design tool that helps us hone our process. With that in mind, our panel tackled some tough questions, including:

What is intersectionality and why is it key when talking about inclusion?

Intersectionality is an approach largely advanced by women of color, arguing that classifications such as gender, race, class, and others cannot be examined in isolation from one another; they interact and intersect in individuals’ lives, in society, in social systems, and are mutually constitutive.

It’s important to understand that not everyone’s barriers or experiences are the same and, that each intersection of race, gender, and ability results in a distinctively different interaction between privilege and oppression.For example, a white male with a physical disability experiences inequality differently than a female of color with a physical disability. Each intersection results in a distinctively different level or lack of privilege.

In order to design in the most equitable and inclusive way, we must focus our work on understanding these intersections so that we can center on those who experience the deepest disparity.

How can designers go beyond standard guidelines to provide more inclusive products, spaces, and communities?

While the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability, from a design perspective, the ADA standards for accessible design are not law — they are a set of guidelines open for interpretation. Additionally, the guidelines are focused on addressing few disabilities – primarily those users in a wheelchair, or with visual impairment. It does not adequately prepare designers for the multitude of barriers or different abilities that should be considered in design process and solutions.

Designers should take responsibility to educate themselves and others to think outside their own frame of reference. Panelist Martha Clarkson brought up an example from her own work experience in which a colleague pondered aloud why a person with a visual impairment might require braille in a copy room - because why would “those people” require access to copy supplies? This is a case of implicit bias, where an individual is illustrating their lack of understanding for ability outside their own.

Understanding that we all hold implicit bias, designers must move beyond guidelines and continuously seek to better understand barriers felt by a diverse range of people. We bear the responsibility of creating equitable products, spaces, and communities – therefore the onus is on the design community to reevaluate both the design process and practice, and to continue to learn from the outcome.

How do we change the work of design to prioritize inclusion and reflect the communities we serve?

Historically, and still today, the architecture, engineering, and construction community lacks diversity. How can we expect to design for all if all aren’t represented in the process? When teams include people from a multitude of backgrounds and seek the perspectives of community organizations, local government, and individuals throughout our cities — particularly with those who have been historically underserved — we are able to approach design challenges in a more inclusive and equitable way.

However, no matter how great the diversity practices of an organization may be, an inclusive design process cannot happen solely within the walls of a design firm. The key to changing the design process is going beyond the way we build our teams and engaging with our communities.

What can be done to address racism and implicit bias through the design of our City and how can those sitting in the room be advocates and allies for this change?

As panelist Joy Alise Davis, a design strategist, noted, the Black community needs accomplices — not more allies — who are willing to work in collaboration to disrupt the city’s deeply entrenched issues. Overwhelmingly, the panelists agreed there is no one place in our city where people of color feel safe and free to be themselves.

Portland and the state of Oregon have a deeply rooted history of racism that has created systemic issues in policy and urban planning which have disproportionately affected communities of color. Portland’s reputation as a progressive city only serves to further enable us to mask these systems that are still in place — meanwhile we see continued gentrification displacing people of color. This is resulting in dispersion to outlying areas of the city, where resources cannot be as readily accessed, and the concentration of historic community centers is compromised.

As designers shaping the future of cities, we have a responsibility to seek out partnerships with our communities of color and play an active role in challenging unjust policies.

How can designers better engage with their communities and those impacted by the work they produce for a more inclusive outcome? How can they ensure they are providing power, a voice, and decision-making authority to a variety of people, particularly those who do not have a place at the table now?

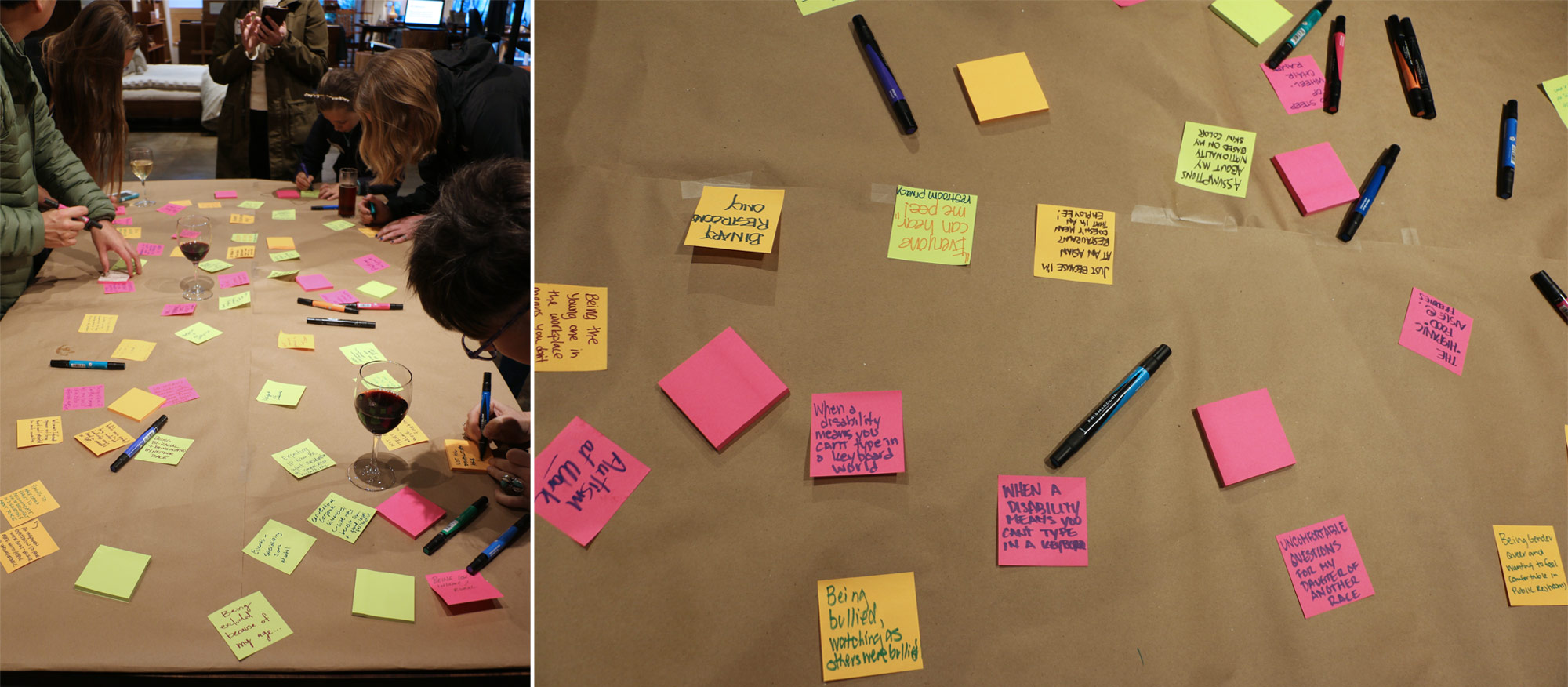

Contrary to common practice, community engagement does not begin at project kick-off. Designers should get in the practice of conducting research and active-listening exercises before a project even begins. Research is the first step to understanding the history, politics, and social constructs of a community; it can also inform how and by whom a community has previously been engaged. Active listening offers an opportunity to build on previous engagement to better understand the challenges and desires of a community firsthand.

An important consideration of the research and active-listening exercise is understanding what has already been asked of a community so as not to cause survey fatigue. Ensuring that community voices are being heard is only a small part of the equation. To truly disrupt the system, the power structure must be radically shifted so that all those with decision-making authority are all those affected by decisions.

Where we’re going:

Resolving the need for — and finding the right approaches to — equity, diversity, and inclusion in design is larger than a two-hour conversation, and while the discussion didn’t pose specific solutions, attendees and panelists agreed that we have much more to learn from each other at every step of the design process. A first step is recognizing the social role and responsibility we hold as designers, and being aware of the importance that diversity and inclusion play in the creation of equitable places, things, and experiences.

Ultimately, we hold the responsibility to address our biases, understand the existing environment and injustices of the communities in which we work, and change our design processes to create a better future for all.