The 600-Year Office

How can we design offices that plan for future uses and adaptations, rather than just the way we work today?

Editor's Note: ‘The 600 Year Office’ was presented at the BCO NextGen Ideas Project 2023: Finalist Showcase in 2023 and was first published in an analysis piece by Property Week.

There’s a good chance that I will outlive the first office building I worked on.

At my first job out of architecture school, I worked on the design of two large office towers. These 180m tall buildings were completed when I was in my early 20s — and designed for a 60-year lifespan. The structures of these towers, constructed from tens of thousands of tonnes of concrete and steel, are perfectly capable of lasting well over a century, potentially even hundreds of years. How is it possible that they could be around for less time than I will?

At Gensler, we’ve been exploring the potential for rethinking designed lifespan of the buildings we design. How can we make better use of the embodied carbon in our built environment by extending the life of the most carbon-intensive elements of office buildings? How can we design offices that plan for future uses and adaptations, rather than just the way we work today? I asked the question: instead of planning only 60 years in advance, what would it look like if we designed an office building for 600 years?

The 60-Year Lifespan

Over recent decades, the 60-year lifespan has struck a balance between efficiency with costs and materials, and the need to keep our workplaces up to date. But we’re at a different point in history now, and there’s two important reasons why 60 years is no longer an acceptable default for designed lifespan:

On the one hand, embodied carbon is the most important factor for our buildings to beat the climate crisis — if we can make the most carbon-intensive elements of buildings last longer, such as the structure and basement, we’re giving our initial carbon investment more time to pay off. Put simply, since steel or concrete structures have the potential to last a hundred years or more, designing with a plan for only 60 is inherently wasteful.

On the other hand, the way we work is transforming faster than ever before. At Gensler we have insights and research that give us a clear picture of how we’ll work in coming decades — but the way we work will change so much in 60 years that it’s impossible to say with any certainty what the workplace of the 2080s will be like. We have a whole architectural studio working on transforming existing office buildings in London which are no longer attractive to today’s tenants — many of which are just three to four decades old, and already obsolete.

This presents a paradox — we want the most carbon-intensive elements of our offices to last much longer, yet we need them to be suitable for a future that will change beyond what we can imagine in just a few decades. I’d like to imagine a new way of approaching office building design that can achieve both of these goals.

The 600-Year Office

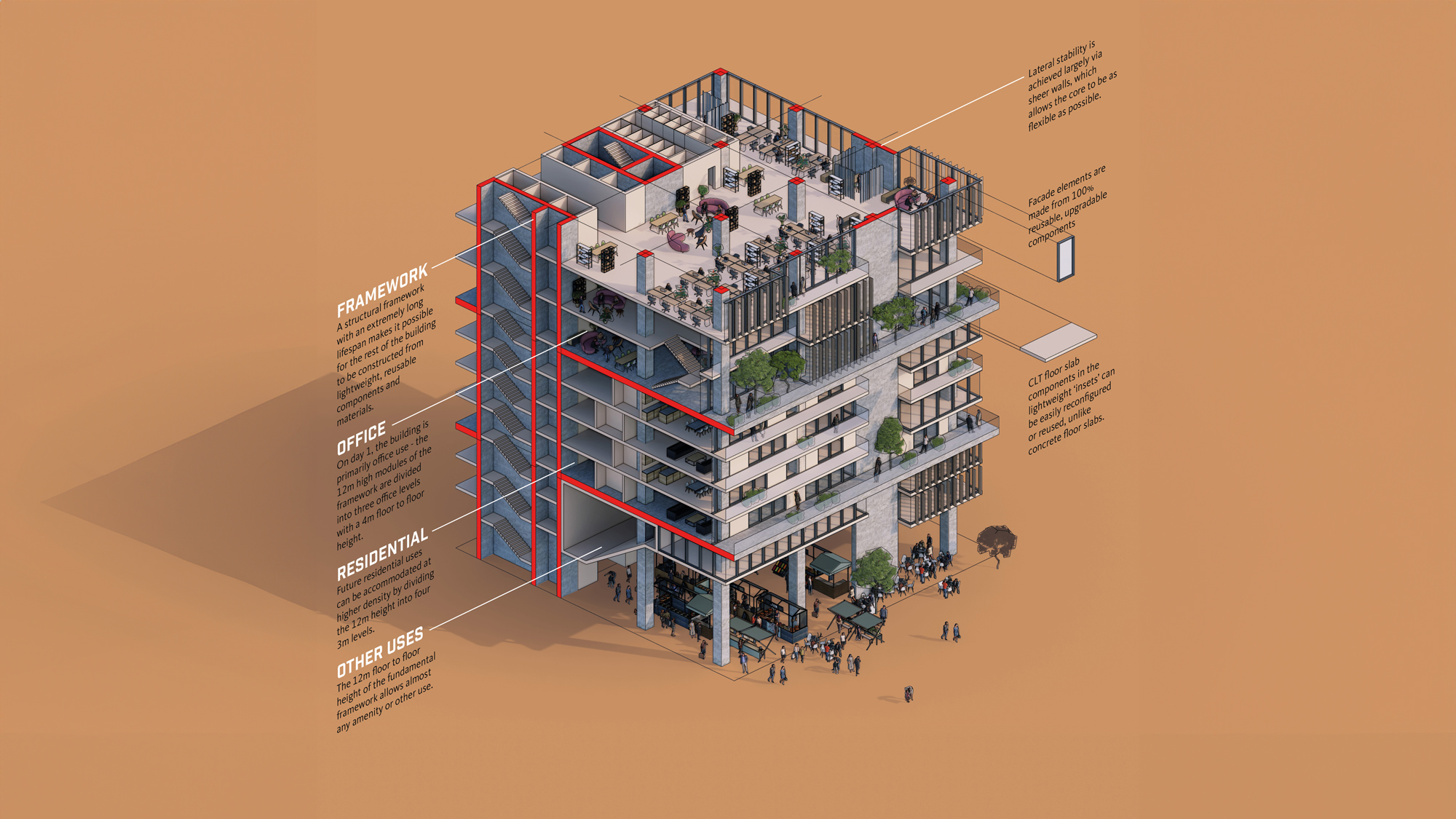

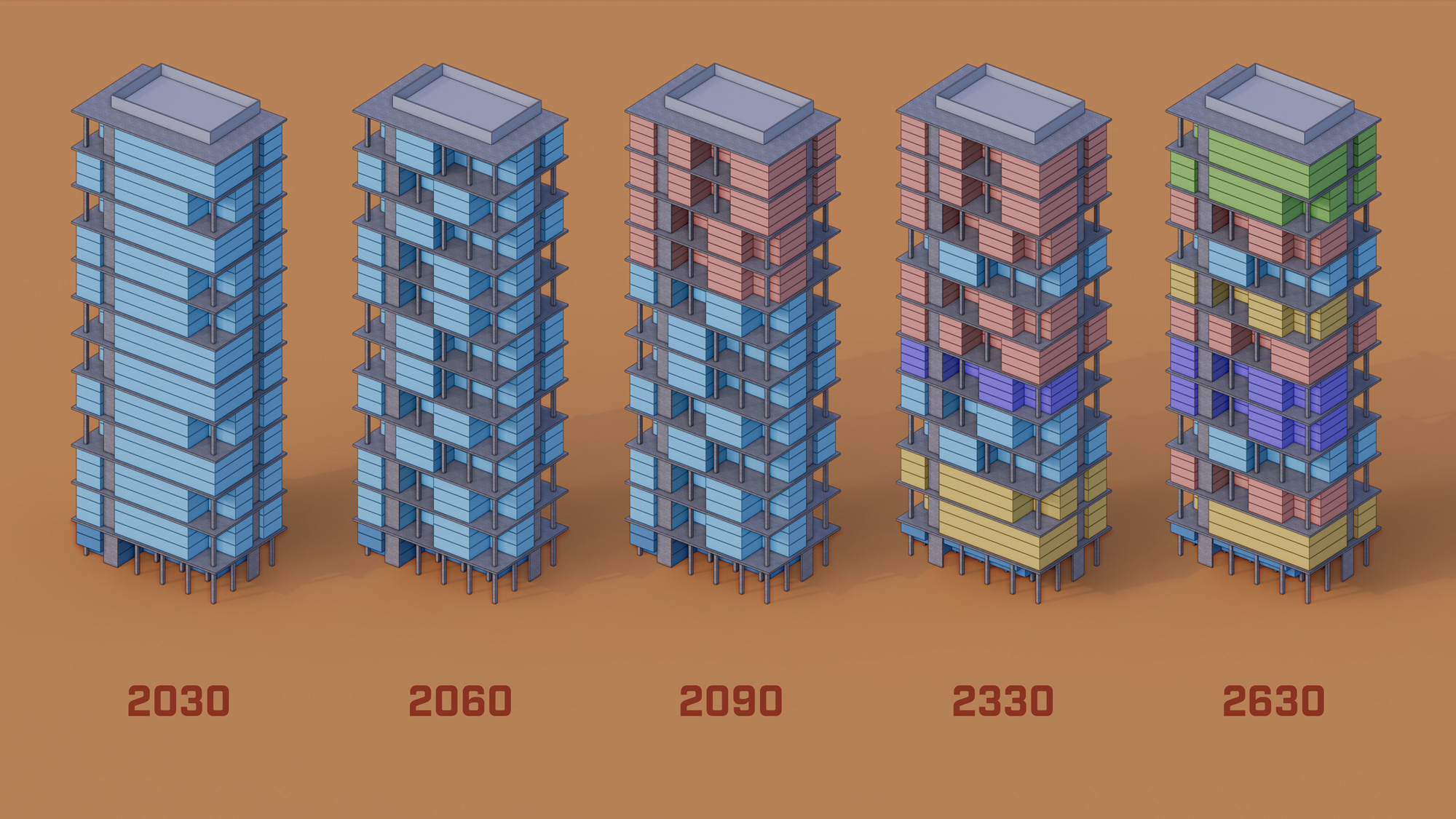

The Year 2030: The 600-year office welcomes its first occupants. This building is designed around a fundamental ‘framework’ structure with a very long lifespan, and lightweight ‘inserts’ that have a shorter lifespan and can be reconfigured as requirements change. The framework is far more adaptable than the structure of a typical tall building, with slabs every 12 metres, meaning each vertical module can accommodate three office levels, four residential levels, or two levels of another use, such as a building amenity. On day 1, our office building is a single-use office, but with a plan for multiple future uses and adaptations.

The Year 2060. London has a climate similar to Barcelona today. All vehicles in central London will be electric, which will make the city quieter and the air cleaner. It will be 20 years since anyone in our building worked all day behind a monitor at a desk. This means that the outdoor working trend we saw the start of in the 2020s has expanded dramatically — users expect to work outdoors all day when the weather allows. The 600-year office was designed with a plan for this change in mind: office spaces can be easily reconfigured to enhance and expand outdoor workspace.

The Year 2090. The way we work has transformed — but our homes will be very similar to today. The building has a plan to reconfigure some or all levels as residential and other uses as required. This is possible due to the design of the building’s core, which allows lifts and services to be reconfigured, whilst the 12-metre vertical ‘module’ means that the developer gains floor area from this change, making it far more viable.

The Year 2330. The 600-year office is now a truly mixed-use building, including uses that we don’t typically see in tall buildings today, such as manufacturing. In the 24th century, resilience to extreme weather is key for any tall building, and this building has several strategies, including a more flood-resistant ground floor.

The Year 2630. In this building’s 600th year, it will likely have completely new uses. What if, in the year 2630, significant portions of the building are now used to improve London’s biodiversity, rather than accommodate humans?

The 600-year office concept is a bold vision that pushes my questions around designed lifespan to the extreme — but there are clear strategies here that can be used on all of our projects. By leveraging our research and thought leadership to lay out several future scenarios and design a ‘framework’, with a long lifespan capable of supporting them, we can design buildings that are far more adaptable than any buildings of the past. We firmly believe that, with today’s technology and infrastructure, it is possible to construct buildings that extend the lifespan of their carbon-intensive structure, whilst being adaptable enough to thrive in an uncertain future.

For media inquiries, email .