Why We Need Bold Change to Revitalize Our Cities

October 27, 2023 | By Maurice Reid and Ian Roll

It is clear that our cities’ downtowns are suffering. As we emerged from the pandemic, the common assumption was that once we could safely return to the office, the problems associated with limited office occupancy would be solved. That has not proved to be the case. Office work has shifted, and business and employee habits have indelibly changed.

To date, ideas to reverse the downward trends have been relatively conventional. A common response is to create more compelling office space centered on experiences. Another trend is “flight to quality,” with leasing activity and movement of new leases moving to Class A buildings in prime locations with the right mix of high-quality amenities. But a walk through even some of the most compelling offices with the best amenities reveals low attendance.

It’s time for bold change to remake our downtowns. Just as Georges-Eugène Haussmann changed Paris in the late 19th century, now is the time for radical change. This moment is an opportunity to remake our cities for long-lasting, resilient futures.

Office-to-Residential Potential

The office to residential prospective is a compelling idea to transform underperforming office buildings into vitally needed housing and breathe new life into downtowns. Gensler’s conversion suitability algorithm reveals that about 25% of buildings across North America are potential candidates for conversion. However, the issue of cost has yet to be cracked. While these conversions are an essential element in the revitalization of downtowns, it’s clear this isn’t the only solution since 75% of these buildings are unlikely candidates.

The trouble is that downtowns today are monoculture based and dependent on the success of office buildings. While the demand for office space has abruptly shifted, the long-term trend is decreased demand. A recent Cushman Wakefield report estimates there will be an excess of 1.1 billion square feet (about the area of Manhattan) of office space by the end of the decade. This is a combination of 740 million square feet of natural vacancy and 330 million square feet attributed to remote and hybrid strategies. More immediately, CoStar reports 55% of leases active in January of 2020 haven’t yet expired. It can be expected that an additional wave of change is yet to come.

Everyone living in a city should be concerned because the issue isn’t isolated to those who own commercial offices buildings. While our local governments may be losing tax bases, our communities are at risk of losing identity. How do people recognize a city without an iconic skyline? What does it mean if we have no town square to celebrate our championships or holidays?

From Purpose-Built to Flex-Built

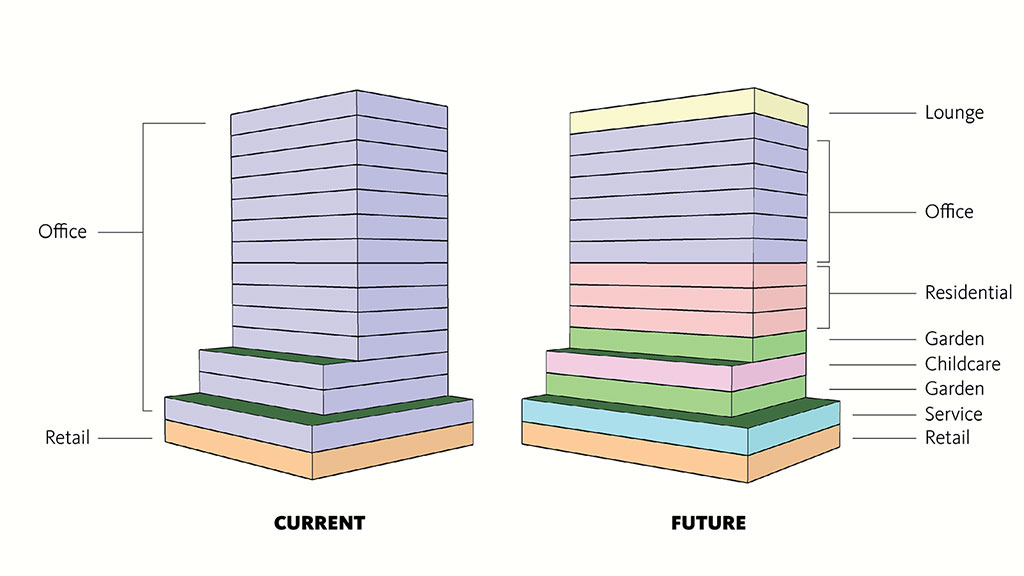

The next step, from the design and usage side, is to become more plastic in our thinking. Even if a building successfully converts to residential, its work-from-home tenants will be using the building as an office for a portion of the day. Maybe buildings shouldn’t have binary classification as either office or residential, but instead should be considered a structure with functions that can be modified over time.

An immediate evolution of the office building could be a direct response to the challenges many office workers face when returning to the workplace. The pandemic led to new habits of significantly greater convenience as we became more neighborhood centric in the range of our daily lives. Transitioning back to work downtown means a return to dropping kids off at school, dealing with a pet, getting lunch, and running simple errands. Underutilized buildings could immediately adapt to provide many of these services in proximity to our downtown offices. Imagine a building that combines child and pet care, groceries, dry cleaners, and leisure and entertainment.

Restore Ecosystems — Literally

While much consideration is rightfully given to repurposing existing office buildings, there is also a percentage of buildings that are functionally and structurally obsolete. In these cases, renovating for improved efficiency and use may not make cultural, environmental, or economic sense, and demolition may be an inevitability.

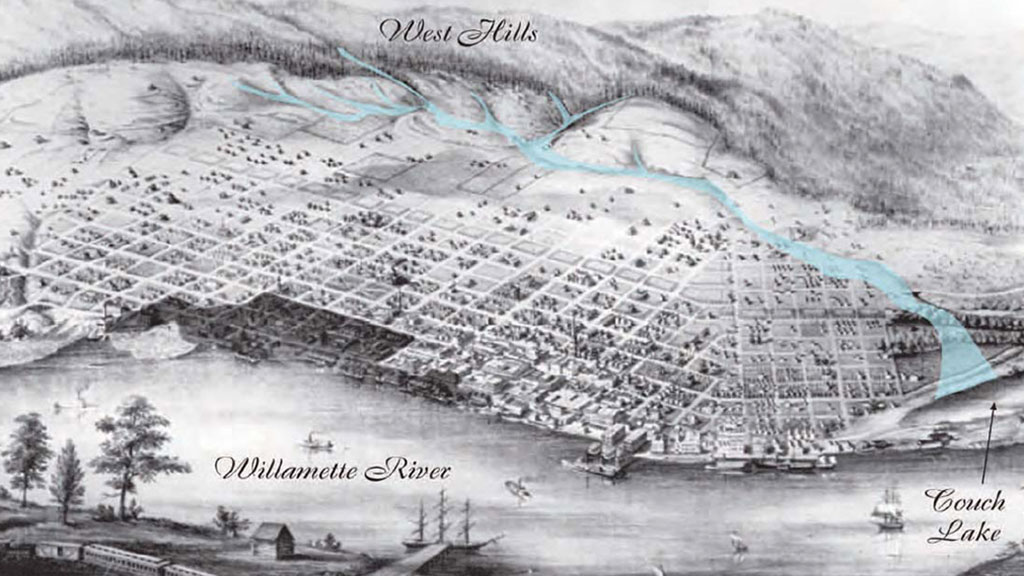

Many city centers were built at the confluence of natural features that were diverted as downtowns matured. In Portland, Oregon, Tanner Creek once flowed from the west hills to the Willamette River, traversing what is now the city center. Over time, downtowns became hard, urban environments without biophilic qualities and became significant contributors and creators of detrimental environmental conditions, storm water runoff, and urban heat island effects.

The remaking of downtowns should rebuild green space into cities. Gardens could be brought to urban centers, either in place of former buildings or on top of underutilized surface or structured parking. The storm water swales already implemented in many cities could be expanded into larger rain gardens, also leading to habitat creation. While Tanner Creek is unlikely to entirely return to Portland, a network of natural spaces could serve as an ecosystem thread throughout the city.

New Paths to Ownership

The equity investment ownership model of many buildings is a considerable obstacle to changing downtowns today. When equity comes from investment funds separate from communities, the value proposition is a simple black and white consideration and investment quickly moves to more advantageous places. If the proposed renovation doesn’t return a profit, there is no other incentive to move the project forward. But local communities can’t move, and for them, the consideration is entirely different.

Our communities are worth more than a straight investment pro forma analysis, and we must consider paths to building ownership in which local people and businesses have a direct financial stake in the overall viability of their communities.

A recent Washington Post article outlines how millennials are pushed to the sidelines of conventional homeownership. Office-to-residential conversion could be an opportunity to expand the sidelines. Instead of building financial models for private equity conversion of office buildings, we could instead incentivize cooperative ownership of conversion projects and open opportunities for new home buyers to enter the market.

Much like co-op ownership of residential buildings, a co-op ownership of an office building by business tenants would lead to local stakeholders who naturally have an interest in the success of the city. Businesses would also have a chance to build wealth though equity growth. These buildings could be rich in shared amenities, meeting spaces and services, and provide flexible office and open work areas to allow shifts in business size. The design approach would be much like cowork models but instead of temporary leasing arrangements, businesses could have a rent-to-own stake in the building ownership.

While office-to-residential conversion continues to be a compelling and productive conversation, we encourage more expansive thinking and a vision of downtowns that are a mix of uses serving people, planet, and prosperity goals. While there are points of concern for the current state of our city centers, this is also an exciting and once-in-a-lifetime chance to create meaningful and lasting change.

For media inquiries, email .